Attenborough's Political Corruption of Science

Sir David pushed the climate narrative to aid a WEF agenda

As we in Canada face an election with the horrify possibility of installing a stakeholder-capitalist (World Economic Forum), net-zero and digital currency-promoting climate zealot as our Prime Minister (i.e., Mark Carney), I thought I’d share Chapter 12 of the book I published in early 2022, Fallen Icon: Sir David Attenborough and the Walrus Deception.

It summarizes my research on how, beginning in early 2019 (after year of planning), Sir David Attenborough used 10 documentary films—financed by activists at the World Wildlife Fund—to push his radical climate change views on the wealthy and powerful members of the WEF (including Mark Carney), in addition to manipulating public opinion.

As a biologist, it was an eye-opening journey into the world of elite politics and influence-peddling—and its impact on the integrity of science. It may do the same for you.

These are simply my concluding remarks, my final chapter.

For the details and references, Fallen Icon is available through Amazon at these links: US link; Canada link; UK link

The Icon Falls

COP26 [the 2020 UN climate change conference, held in Glasgow in 2021] ended up a bitter result for Attenborough and his supporters. Given what they’d hoped to accomplish, it was a failure, as even staunch British environmentalist George Monbiot has admitted.

Three years of hard-hitting public statements and ten propaganda-filled documentaries that misrepresented science had gotten Sir David nowhere.

Although even a few months beforehand, Attenborough’s position appeared to have massive support, it turned out that securing agreements for the ambitious climate action plans he was after was more difficult than he had anticipated.

Third world nations were still demanding billions from developed countries for adaption to climate change but now western governments were cash-strapped from dealing with their responses to the pandemic. Most critically, there still wasn’t the international support needed: China and India both rejected severe restrictions.

Attenborough seemed particularly reticent to speak after news of the weak COP26 final agreement was made public. I could find only one interview with him after the meeting ended and in it, he made a vague statement that could perhaps be taken as a reference to the COP26 outcome:

Sir David feels glad to have helped raise climate awareness through his documentaries and thinks there is hope for a healthier world.

“I believe TV is really very important from that point of view,” he says.

“It is essential. We’re only going to get out of this mess if nations get together and say ‘We’re facing a crisis’.

“Yes, I do think that the world is coming to its senses.

Whether it comes quickly enough and clearly enough is of course the problem.”

However, his most dedicated supporters seemed not to have blamed Attenborough for the failure of COP26 to generate an earth-shattering international agreement: a poll taken by an eco-energy company just after the meeting ended found Attenborough topped the UK public’s list of inspirational ‘green’ celebrities, beating out Greta Thunberg (second place), Leonardo DiCaprio (seventh place), Prince William and Prince Charles (‘in the top ten’).

Obviously, for some the UK’s ‘national treasure’ could still do no wrong.

However, others like me could see that Attenborough had not only failed to secure his legacy but had demeaned himself in the process.

He wasn’t the only one in history who has succumbed to this inevitable fate of noble cause corruption – and certainly won’t be the last – but he has been the most high-profile example in recent years. I knew another example from my work with polar bears and the similarities are striking.

I had shown in other work that the 2007 USGS forecast for future polar bear survival had failed spectacularly. Before the ink was dry on the prediction report, September ice extent dropped suddenly to levels not anticipated until 2050 – and remained there for a decade – yet global polar bear numbers may actually have risen.

Through that analysis, I learned that the scientist who played the largest role in getting the polar bear classified as ‘threatened’ on the US Endangered Species List – former USGS biologist Steven Amstrup (now at Polar Bears International) – was not only intensely proud of this achievement but was fêted with awards. One came with a substantial amount of cash ($100,000 for the Indianapolis Prize in 2012) and another elevated him to rock-star status (for a BAMBI award, also in 2012).

Amstrup’s accomplishment depended upon a computer model that was fed his (and only his) assumptions and personal opinions regarding what polar bears would do in response to markedly reduced summer sea ice – treated by the model as facts – which in turn depended on untested model predictions of future Arctic summer sea ice coverage. Despite the high probability of the interconnected models being false due to their inherent uncertainty, the final output was accepted as a scientific result.

Opinions and assumptions had to stand in for facts in the polar bear model because dramatically low sea ice coverage had not yet occurred while the bears were under study: no one knew for sure what effects such reduced ice would have. In other words, in the face of uncertainty due to lack of data, it was considered scientifically acceptable for opinions and assumptions to masquerade as facts.

Modelling of this nature is an increasingly common approach that is very worrying for conventional scientists and the public alike, a topic I’ll return to later in this chapter.

However, having polar bears declared ‘threatened’ on the basis of this model result was not enough for Amstrup.

What he appears to desire is a career legacy that gives him credit for spear-heading greenhouse gas emissions legislation being pushed through in the United States (something which has still not happened). He has become so focused on attaining that political goal – and defending it fiercely – that nothing else matters.

I saw the same Amstrup legacy-building syndrome in Attenborough, except that Sir David was not only richer but far more influential. He also had a much grander goal: it seemed that nothing less than changing the way that society operated would be quite good enough.

He wasn’t a scientist like Amstrup but Attenborough thought he had science behind him because he believed what the WWF told him was true.

Both men wanted to be remembered for saving the world with what they considered to be a science-based argument – or at least, for playing a big part in that salvation.

I’ve come to conclude that for men like Amstrup and Attenborough, the closer to the end of their careers they get – Amstrup is now 71 and Attenborough is 95 but both are still professionally active – the more desperate they become to accomplish their legacy goals, regardless of what is required – including discarding the public trust they had previously cultivated with care.

Ultimately, it seems hard to attribute such behaviour to anything other than vanity.

When viewed from afar, the agenda-driven narratives Attenborough has been spinning over the last few years certainly seem characteristic of legacy-seeking. Since 2018, he has taken on a distinctly pessimistic view of the world with unexpected fervour and promoted it aggressively.

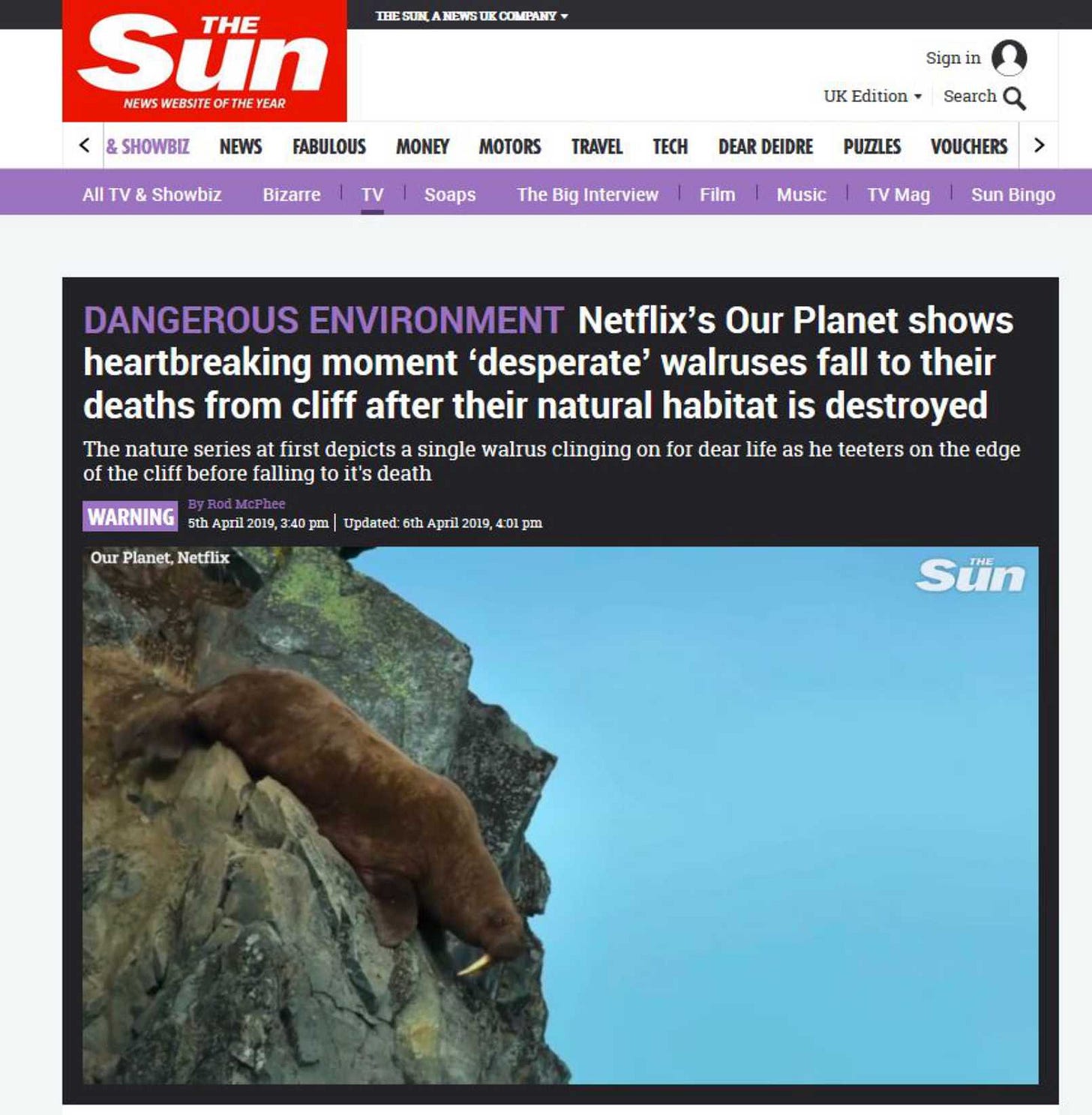

I was truly shocked to see the raw brutality of the falling walrus footage in Our Planet, so uncharacteristic of an Attenborough film, be used to kick-start a hardline political climate change mitigation campaign.

It was a bomb used to get the worlds’ attention.

I can only conclude that using the footage in this way was deliberate because it required such strategic planning and timing to attain. Moreover, the sequence had a distinct World Wildlife Fund-style flavour to it because the WWF had been given so much control in its production.

We know that the WWF had knowledge of the recurring phenomenon of polar bears driving walrus over the cliff at Cape Schmidt as early as 2011 because they had paid informants on the ground nearby. It was therefore highly likely that this information was one of the critical assets this organization brought to the Our Planet project.

It seems highly likely the WWF were the ones to approach Netflix about a film that included this phenomenon, although perhaps they approached SilverBack Films first and together the pair pitched the idea to Netflix.

However, by 2015 the Our Planet series, with all collaborators except Attenborough and the BBC acknowledged, was announced. Coincidentally or not, this was the same year Attenborough signed on to the WWF as an official ‘Ambassador’.

As I pointed out in Chapter 1, WWF not only provided the funding for the series, it was also instrumental in getting film crews to a number of remote, restricted-access locations (including the Russian walrus haulouts) and was allowed to apply their unique brand of conservation ‘science’ to the entire project. This gave them a huge amount of control over the final product. In fact, one could argue they held the upper hand.

It was obvious that Attenborough trusted the WWF absolutely and Attenborough’s high opinion of the organization seemed to have rubbed off on the rest of the partners.

The two owners of Silverback Films, Keith Scholey and Alastair Fothergill, had produced documentaries for the BBC with Attenborough for years before they branched off on their own. Attenborough seemed to have had as much trust in them as he had for the WWF.

This tight circle of collegial experience, with Attenborough at its centre, made possible the historic deal between Netflix, the WWF, Silverback Films, and the BBC to share footage of the critical walrus incident, filmed by a joint crew, between the Our Planet series (produced by WWF and Netflix) and Seven Worlds series (produced by the BBC).

Seven Worlds showed polar bears driving hundreds of walrus over the cliff edge at Cape Schmidt but Our Planet, released six months earlier, showed walrus falling off the cliff to their deaths without the impetus of predators, instead laying the blame squarely on climate change.

It is therefore inconceivable to me that the WWF, Silverback Films, and Netflix did not have Attenborough in mind as narrator for Our Planet as soon as the project was conceived prior to 2015.

Which means it’s also highly likely that both Attenborough and the BBC were included in discussions about the walrus episode even before the series was announced to the public in 2015, although we cannot be sure.

That said, the presence of a BBC director/producer and two BBC cameramen on the Silverback Films expedition to Russia in 2017 strongly suggests there had been a plan in place from at least the time of the series announcement in 2015 to split the final walrus footage between the Our Planet and Seven Worlds projects. This conclusion is based on comments made by Sophie Lanfear regarding the two and a half years it had taken to plan the expedition to Russia.

Significantly, as I mentioned in Chapter 2, Silverback Films producer Keith Scholey was quoted as saying that they ‘knew’ as soon as they saw it that the falling walrus scene ‘was going to be the footage that would become most associated with the climate change horror that’s happening to Arctic species.’

In retrospect, it appears that they didn’t so much ‘know’ this would happen but rather, they developed a calculated plan to make sure it did.

However, I have shown in this volume that most of what was said and implied about walrus in the Our Planet sequence was misleading or inaccurate. This is not surprising given that years before the film aired both the WWF and scientific advisor Anatoli Kochnev were pushing a decidedly pessimistic and largely false version of Pacific walrus conservation biology.

Unfortunately, Attenborough, Silverback Films and BBC script writers assumed that the WWF science provided to them was up-to-date, accurate, and unbiased – but it was not.

For example, it was misleading to say that walrus would not have been on land if not for lack of sea ice due to human-caused climate change or to imply that land haulouts are somehow new or ‘unnatural’ for walrus.

We know that historically Pacific walrus herds of females and calves have used ice-free beaches as haulouts even when sea ice over shallow water has been available – and that most walrus males leave the ice after mating in the spring to use ice-free beaches in the Bering Sea until the following winter. Walrus can and do feed just as easily and successfully from shore as they do from sea ice and this has always been true.

It was also dishonest to claim that walrus were forced by lack of space to crowd close together on the single enormous haulout at Serdtse-Kamen shown in the film: walrus prefer very close contact wherever they haul out, even if there is room to spread out.

Moreover, the small herd of approximately 5,000 walrus did not choose the cliff haulout at Cape Schmidt in 2017 because they there was no space for them at Cape Serdtse-Kamen, as Attenborough implied in his narration. Not only was there ample space available at Serdtse-Kamen (which is a beach complex 20 kilometres long) but movement of the animals along this coast in the fall is the other way around, from Cape Schmidt to Serdtse-Kamen. Accordingly, the Netflix/BBC crew were at Serdtse-Kamen in October after finishing their filming at Cape Schmidt in September.

Lastly, hundreds of walrus did not die at Cape Schmidt because they wanted to join the herd in the water and had no other way to get down, as Attenborough claimed in Our Planet: that was outright dishonesty. At most perhaps a dozen or so died this way and rest of the several hundred dead walrus shown in the film died days earlier when polar bears frightened them over the cliff, as was shown in the Seven Worlds BBC documentary six months later and described in the 2017 Siberian Times article discussed in Chapter 4.

Unfortunately, Attenborough, Netflix and the BBC assumed (as National Geographic had done before them with the starving polar bear video described in Chapter 8) that the public would not be turned off by inaccuracies and obvious falsehoods about animal victims of climate change. However, it seems they were wrong on this score.

In addition, Attenborough, the WWF, Netflix and the BBC all assumed that they could make people care more about climate change by using horrifying images and relentless messages of doom. But they were incorrect on that as well.

How many people thought the Our Planet statement that hundreds of walrus fell to their deaths from a Siberian cliff because of climate change was absurd? How many others believed it must be true because it was uttered by Attenborough, a person they thought they could trust?

And how many people ultimately turned against Attenborough and the message he was trying to deliver because of the deception and emotional manipulation that was eventually revealed? I’d guess quite a few.

It doesn’t really matter exactly when Attenborough realised that the WWF had a plan to use falling walrus deaths as a political cudgel in the climate change war but it does matter that he agreed to do the same.

Most people realise that a documentary filled with big-eyed babies and jaw-dropping scenery does not fully reflect the reality of the natural world, where accidents happen and predators kill and eat their prey. But the walrus-falling-to-their-deaths scene was something else: it was gratuitous animal tragedy porn.

There was no need to show a half dozen animals die an agonising death in slow motion – except for the political agenda.

This scene had WWF written all over it because that’s how they do business. Their organization’s primary goal has always been to generate donations and they have discovered over time that what works best is emotional blackmail.

So when Attenborough agreed to this strategy – something he had never resorted to before – he showed his hand. He showed us all what he was prepared to do to achieve what he wanted.

He was not trying to make a point that nature can be harsh: he was delivering a political message he wanted people to never forget.

The fact that Attenborough ultimately failed to achieve the legacy goal he appeared to have set for himself didn’t mean the walrus ruse was not a success for everyone else involved. Within about a year of its release, the falling walrus film sequence and subsequent media attention had resulted in huge benefits.

Netflix got boosted subscribers and acquired a new ‘sustainability’ advisor (Johan Rockström, the climate ‘tipping point’ guy).

The WWF got boosted donations but more importantly, future deals that gave them executive control over similar climate change propaganda films marketed as entertainment. This was a huge win for them and clearly one of their primary goals: this fund-raising organization, as

always run by savvy businessmen, is now firmly embedded in the documentary film industry.

Silverback Films got a lucrative buyout a mere seven years after Alastair Fothergill and Keith Scholey pulled out of the BBC. The producers were still in charge but massive funds were injected into making similar climate change projects.

Producer/Director Sophie Lanfear became an Emmy-award winning director at an incredibly young age.

Kochnev almost certainly got more cash in foreign currency for his part in the filming than he ever believed possible for a Russian government scientist working in the remote Far East. I know from discussions with a Russian colleague in a similar situation that these employees take home a salary that is broadly equivalent to minimum wage – barely enough to keep them alive and certainly not enough to ever get ahead.

The BBC seems to have garnered the confidence boost and determination it needed to continue doing more hard-hitting climate change documentaries.

Even Attenborough, at least initially, seem to get everything he could have wanted: even more notoriety plus his second and third Emmys in two years (for Our Planet and Seven Worlds). In the end, he also got an appointment by the British government to speak at COP26.

None of it would have happened without the shock value of the falling walrus sequence.

It was only Attenborough who didn’t achieve the goal that was most important to him: seeing a ground-breaking result at COP26 that would change the world.

However, the unique alliance that was formed then between Netflix, the WWF, Silverback Films, David Attenborough and the BBC to produce Our Planet was not just an auspicious occasion: it was also the beginning of a new strategy to influence public opinion and ‘nudge’ political policy through message-laden documentaries passed off as entertainment. This form of propaganda is not going to stop despite the poor showing at COP26 and Attenborough’s failure to secure a legacy.

The ten documentaries that came out between 2019 and 2021 – all on the same theme, many with the same producers, but all narrated by Attenborough – were filmed over the same few years and released at calculated intervals with copious media attention, all aimed at securing an international climate deal at COP26 in 2020. The unexpected appearance of the Covid-19 pandemic threatened to derail the plan but ended up extending the agenda by another year, to 2021.

Once kick-started by the walrus sequence in Our Planet, these documentaries constituted Attenborough’s aggressive agenda on climate change action. His many media interviews and public presentations were the primary means of promoting the films.

The following list shows just how tight the scheduling of release dates for the documentaries and special episodes were, even with an extra year added:

29 January 2019. Special premiere edition with falling walrus sequence, for WEF in Davos, Our Planet (Eight part series; Netflix/WWF/SilverbackFilms/BBC/Attenborough)

5 April 2019. Our Planet (Eight part series; Netflix/WWF/

Silverback Films/BBC/Attenborough)

18 April 2019. Climate Change – The Facts (Two part series, BBC/Attenborough)

4 November 2019. Seven Worlds, One Planet (Seven part series; BBC/Netflix/WWF/Attenborough)

13 September 2020. Extinction: The Facts (One hour document-ary, BBC/Attenborough)

4 October 2020. A Life On Our Planet (One hour documentary, Netflix/WWF/Silverback Films/Attenborough)

4 January 2021. A Perfect Planet (Five part series, BBC/Silverback Films/Attenborough)

16 April 2021. The Year Earth Changed (One hour documentary, BBC/Attenborough/AppleTV) 161

4 June 2021. Breaking Boundaries – The Science of Our Planet (One hour documentary, Netflix/Silverback Films/Rockström/ Attenborough)

30 September 2021. The Earthshot Prize: Repairing Our Planet (Five part series, BBC/Silverback Films/Attenborough/Colin Butfield from WWF)

31 October 2021. Special premiere edition, the night before COP26 in Glasgow, The Green Planet (Five part series, BBC/Attenborough), general release scheduled for January 2022

Critically, the ten films and associated publicity spearheaded by Attenborough kept climate change issues in the public eye for the three years leading up to COP26.

It’s telling that the plan was initiated by a special premiere episode that featured the horrifying falling walrus scenes and concluded with a similar special premiere episode, both directed at powerful global influencers. This suggests political elites were critical targets for these documentaries and the films were not meant only for public consumption.

However, in his hard-hitting promotion of the invisible catastrophes that supposedly demonstrate the existence of a ‘climate emergency’ – not proposed for some point in the future, but occurring right now – Attenborough has been spreading misinformation, biased opinions, and bad science.

And I’m not the only one that thinks so.

Conditions in the natural world are simply not as bad as Attenborough and the WWF insist. Polar bears and walrus are not currently starving to death in great numbers because of reduced summer sea ice, despite high-profile experts insisting this might happen in the future.

There is no evidence of a great ongoing extinction of named, visible species, although the WWF continue to say there is.

In fact, a good many species formerly driven to the brink of extinction by overhunting have recovered in spectacular fashion, including the polar bear, walrus, sea otter, northern elephant seal, humpback whale, grey whale, and bowhead whale.

Moreover, the scariest and most extreme climate predictions of the future (including the newest models used to forecast polar bear survival) are the ones that get the most media attention and yet these have been shown to be based on quite implausible ‘business as usual’ scenarios that massively exaggerate possible future conditions.

And while it is true that recent sea ice changes have presented challenges for Arctic peoples who had come to depend on a particular coverage of ice to hunt and travel at a particular time of year, this is not a new phenomenon.

The Arctic is one of the harshest environments on Earth for all forms of life, including humans. Change in local weather and sea ice conditions over short and long time frames have always occurred but fortunately, humans and Arctic animals have demonstrated that they are spectacularly good at adaptation.

Similarly, when examined dispassionately, weather disasters have not increased in recent years, despite virtually every storm being blamed on climate change: even the IPCC says so. Weather disasters have always happened and always will – but fossil fuels have not only enabled us to better protect ourselves from their effects but to recover quickly once they have occurred.

Lastly, crop yields for many critical commodities – particularly rice, corn, wheat, and sugarcane – were at or near record levels in 2020/2021, despite (and perhaps partly because of) much higher amounts of human-produced carbon dioxide in the atmosphere than there had been in the 1980s and which had generated many predictions of drought- and/or flood-related crop disasters.

How can climate change be blamed for a catastrophe that has not taken place? How can there be a climate emergency if one is not discernible?

Insisting a climate emergency exists doesn’t make it so, no matter how often or loudly Attenborough says it does.

What is even more worrying is that when his hard-hitting climate change films made Attenborough a sought-after media guest, it encouraged him to express even stronger opinions he could not have included in his documentaries.

He used one such occasion to promote a revolutionary concept about how future societies should operate that involved curtailing what he called the ‘excesses’ of capitalism, a utopian vision that many people in the world simply don’t share.

These statements exposed a radical side to Attenborough that hadn’t really been evident before: he seemed to have become a mouth-piece for a fringe political movement populated by wealthy revolutionaries espousing extremist ideologies.

Is Attenborough really one of those wealthy elites who think that other people (certainly not them) are causing the destruction of the environment with their excesses and that the lives of those people must be controlled for the common good?

Such radicals – many of whom are supporters of the World Economic Forum (WEF) and whose company Attenborough routinely keeps – apparently see a global government as the only way to save humanity and the natural world.

At its most basic, this goal of a global government and curbing capitalism is not a crazy conspiracy theory, as some media ‘fact-checkers’ still insist.338 It is a well-developed and strongly articulated concept supported by individuals with enormous political power including (among others) heir to the British throne Prince Charles (and his son Prince William), US President Joe Biden, Canadian prime minister Justin Trudeau, and billionaire Bill Gates, as well as many organizations with enormous wealth including (among many others), all major vaccine manufacturers and pharmaceutical companies, major banks and money lenders (including PayPal, Mastercard, and Visa), the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, internet and social media powerhouses (including Facebook, Google, and Microsoft).

Aggressively addressing climate change has been a focus of the WEF and its supporters for decades and it’s no secret that some of them saw the Covid-19 pandemic as an opportunity for advancement of their utopian agenda. However, despite the power and money behind their fanciful scheme, it is unlikely that anything will come of it – for the same reasons that COP26 failed.

The way I see it, predictive computer modelling, including the tipping point nonsense promoted in Attenborough’s films, has played a huge role in fueling such ideologies. Forecast modelling has muddled the critical distinction between scientific facts (i.e. observations) and assumptions (i.e. opinions).

Widespread use and acceptance of predictive modelling to forecast all kinds of future conditions has contributed heavily to the political corruption of science because it allows opinion (potentially skewed by political ideology) to stand in for scientific facts that are not yet known.341 Uncertainty, which once provided the impetus to keep collecting data before conclusions were drawn, now provides an excuse to accept model results as scientific facts.

Oddly, it’s as if those involved believe that developing and running a computer model that gives facts and opinions equal weight is the same as conducting an actual scientific experiment developed to test a hypothesis – and that the model output deserves the same amount of scientific trust and respect as an experimental observation that can be replicated.

Science is no longer seen as a method of dispassionate investigation of how the natural world works – where constant questioning refines and hones the answers – but a tool to be weaponized for attaining political ends. On that score, this investigation truly opened my eyes.

This politicization of science is evident in the routine use of the phrase ‘the science says’ in defending climate change policy positions. But more terrifying still have been the ‘expert’ scientific opinions that could not be questioned and the predictive models based on implausible worst-case scenarios that have been used, over and over since early 2020, to justify draconian government containment measures for Covid-19 under the guise of a ‘human health emergency’.

The public’s trust in science and medicine now appears to be at an all-time low. People who had been blind to the abuse of science rampant in the climate change narrative have had their eyes opened by the pandemic response. These things cannot be unseen.

In a worrying trend, traditional scientists struggle to be heard or have their concerns and criticisms published, both for climate change and Covid-19 related issues, while predictive modelling projects seem to gobble up grant funds and media attention.

Is science as we used to know it already dead? If so, how much of a role has Attenborough played in this progression? Over the last three years, he has used weaponized science presented to a trusting public in a most egregious manner.

My ultimate goal in writing this book is not to denigrate Sir David but to correct the misinformation he has deliberately or unwittingly promoted in his documentaries and public statements.

I am a traditional scientist standing up for science as it is meant to be – without activism and without politicization – because its loss to society will be incalculable.

Over the years but especially since 2018, Attenborough has shown that he lets others do his serious thinking for him and has often placed his trust where it was ill-advised, as he has done with the WWF. By that I mean he has relied on others to present information to him in an easily digestible manner rather than delving into the literature himself.

And having spent a lifetime taking this easy way out, when he decided he wanted his legacy to be something more substantial than ‘a good storyteller’, he seemed to take on the role of spokesman for others with ideological political agendas.

It appears to me that when he agreed to present the gruesome falling walrus film footage in Our Planet as evidence of climate change, Attenborough compromised his principles to achieve a specific end result. Such noble cause corruption is common in the conservation world but it was new for Attenborough.

I am convinced that what Attenborough has done with the falling walrus episode will be remembered long after he’s dead but not for the reasons he intended. It will go down as another ‘own goal’ for the climate change movement and judged as the moment Attenborough fell from grace as a trusted British icon.

The easiest thing you can do to support Biology Bites is to click the “♡ Like”. The more likes = the higher this post rises in the Substack feeds, which puts Biology Bites in front of more readers.

Any thoughts on the other David, Bellamy?