Ritual Dog Burials Have an Ancient History

Most ancient cultures seem to have viewed the spiritual essence of domestic dogs to be very powerful

Here’s something different to think about as we contemplate the new year: that ever since the domestic dog came to be more than 10,000 years ago, many human cultures around the world held its spiritual essence—which was released after death—in very high regard.

[See Bites Out Loud podcast, Episode 14, for the audio version of this essay]

In June 2009, I broke my left shoulder and couldn’t work for almost 6 months. The bone healed quickly enough but the physiotherapy to get the shoulder joint functional again was brutally painful. I got very little sleep during this time but I also needed something other than pain to focus on. I decided to write a book I’d been meaning to write for more than 10 years—a field guide for archaeologists who, while digging for elusive clues about ancient cultures, encounter the articulated skeletal remains of ancient dogs that had died and been deliberately buried.

I knew there were several reference books meant to guide field archaeologists through the process of excavating and identifying bones from the human burials they might encounter, but there was nothing to help them excavate deliberate burials of domestic dogs. Most archaeologists were not even aware that almost since dogs were first domesticated more than 10,000 years ago, ancient people the world over often deliberately buried some of their dogs (see below for more details).

Fortunately, this book would be composed almost entirely of photos that had already been taken, which meant I only had to get the images properly sized and organized. This was important because at first, I couldn’t use my left hand at all and could only type with one finger, which wasn’t very efficient or accurate. But I could use a mouse.

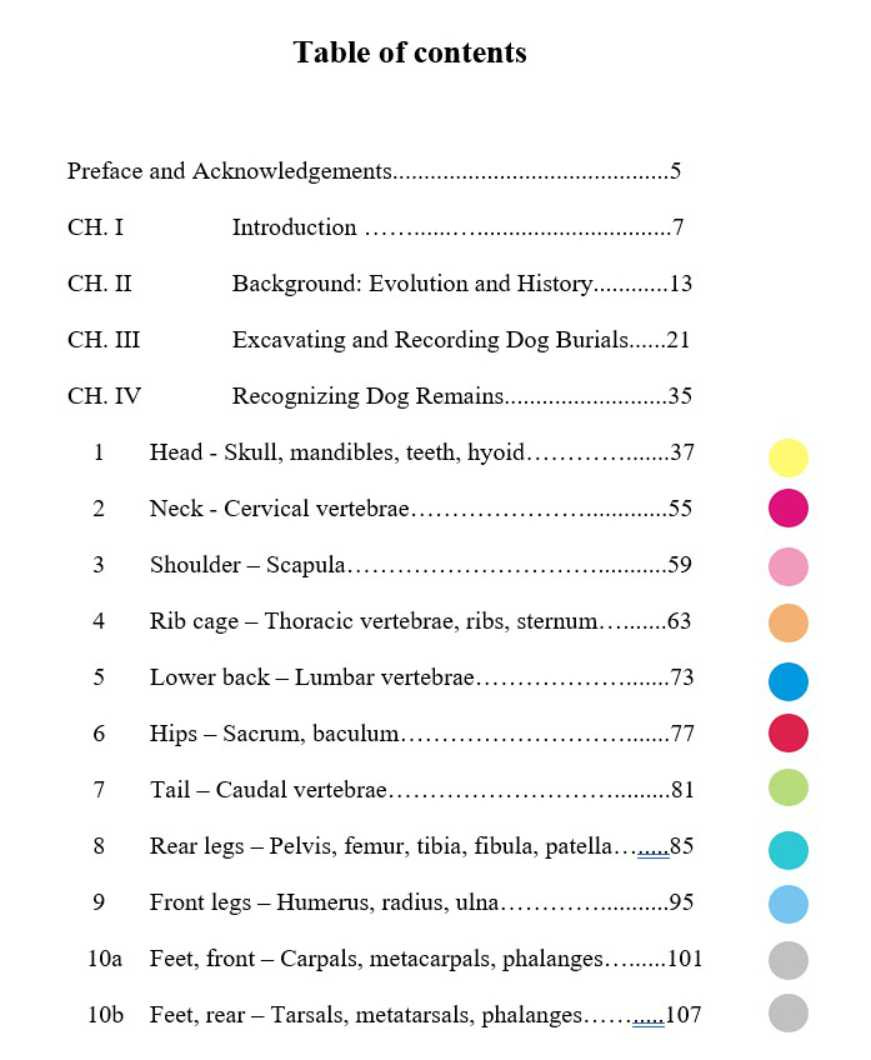

Having this task to complete got me through a very rough time without the need to take drugs for pain. I wrote most of the text in the final few months when I was feeling a bit better. I had the book spiral-bound and printed on water-proof paper so that it could be used in the field even if it was raining; I also colour-coded the chapters to make the bone images easier to find in a hurry.

But now, it seems almost all archaeologists use a tablet or an I-Pad to record data in the field and I’ve had numerous requests recently for a pdf file.

So, as a 15 year anniversary gift to my colleagues, I’ve converted the original files to a stand-alone pdf now available on ResearchGate, where it can be downloaded for free.

Here is a slightly amended version of the introductory text, which explains why the book was necessary.

Why Dog Burials are Important

For 12,000-14,000 years, dogs all over the world have been deliberately interred in ritual fashion. Dog burials have been found throughout North, South and Central America, Greenland, Europe and the Middle East, Siberia and Western Asia, China, Japan, North Africa and Australia. In other words, dogs have been deliberately buried as long as dogs have existed as a distinct species and in every geographic region they came to inhabit. This pattern suggests that interment of dogs may be a fundamental characteristic of the dog/human relationship.

Archaeologically, complete dog skeletons may represent both solitary and multiple dogs in a single interment. They may be formally laid out (positioned) or represent dogs tossed into pits. Remains of complete adult dogs can be found that were buried with very young puppies or with special grave goods (such as food offerings, beads, pottery, etc.). Ancient dogs in some regions or time periods were buried in abandoned dwellings or in close proximity to important dwelling features such as doorways, hearths or chimneys while in other areas, dogs were simply buried in the household refuse that accumulated around ancient communities. Regardless of how they were interred, dogs were buried by virtually all cultural groups throughout their long history.

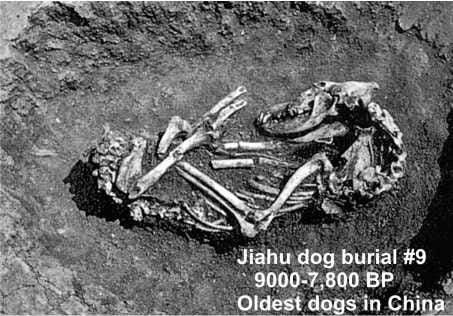

For example, the remains of three dogs found buried together at the Koster site in Illinois (dated to ca. 8,500 BP) are the oldest known deliberate dog burials in North America and some of the oldest known dog remains on the continent. There have been at least eleven equally-old dog interments recovered from the Jiahu site in China from deposits dated to 9,000-7,800 BP. A single dog burial found in Japan at the Kamikuroiwa Rockshelter site is about 8,000-8,500 years old.

Remains of even older deliberately interred dogs have also been found: a single dog burial at Ushki-I in the Russian Far East, for example, is about 10,500 years old and burials 12,000-12,500 years old have been recovered from several locations in Israel.

As often as dogs were deliberately buried on their own, dogs were also included with human interments. Indeed, ancient dogs found buried with humans are more common than many archaeologists realize. Sometimes only part of a dog, such as a head, was included with a human burial. Dogs were interred with human infants and children, as well as with adults of both sexes, which suggests that dogs were not simply being buried with their owners. Dogs were associated with complex spiritualism in many ancient cultures and the practice of burying dogs with humans is as old as burying dogs themselves.

For example, the oldest known dog remains found associated with a human burial are from Bonn-Oberkassel in Germany and are about 14,000 years old. Another early example comes from a site in Israel (11,000-12,000 years old) that involved a young dog or wolf pup (too young for the taxonomy to be certain) buried with an elderly person.

A multiple human/dog interment containing the remains of two dogs and at least seven people has been dated to ca. 6,600 BP and is so far the oldest human/dog burial in North America. Dog remains have also been found with human interments in China and some of these are at least 5,000-6,000 years old.

There are many human/dog interments that are not quite so old from many locations worldwide, including North America and the Middle East. Clearly, the practice of including dogs or dog remains with human burials was once a global phenomenon that cross-cut cultural boundaries in the same way as burying dogs alone.

It seems that virtually the world over, dog spirits were thought to have special powers.

Intriguingly, this concept appears to be as ancient as the dog itself, about 12,000-14,000 years old and may well be inherent to the dog/human relationship. There seemed to have been an almost universal belief that a dog’s spiritual essence, released at death, was very powerful and capable of almost magical feats. Oral histories of several cultures record stories of dog spirits escorting human spirits safely into the next world, providing guidance and protection.

Therefore, it is not especially hard to understand why dogs are included in human burials more often than any other animal or why they were so often carefully buried themselves. It appears that the powerful spirits of deceased dogs were generally treated with care and respect all over the world (even if the living dogs themselves were not) and on many occasions, people attempted to harness that power for specific purposes, such as safeguarding the newly-released spirit of a deceased person on their journey into the next world.

Indeed, it is possible that for most of their history, living dogs did not have specific practical roles but because their spiritual powers were so valuable (and especially strong after death), dogs were tolerated or encouraged to co-habit human settlements rather than being driven off.

Precisely why dogs are universally attributed with such powers may never be known but as I have suggested elsewhere, dogs might be considered to have supernatural abilities if the rapid transformation from wolf to dog (the actual speciation process we call domestication) took place within a human lifetime (i.e. while people watched), as some evidence suggests.

[The idea is that if a person lived long enough to have witnessed the process of a wolf deciding to live amongst people—of its own free will—as well as the eventual transformation of this animal into one with different physical and behavioural features (including white-spotting, flopped-down ears, and being much less fearful of close contact with people), it might be logical for that person to assume this newly-transformed animal possessed a very powerful spirit not found in any wild animal.]

Regardless, much of what we now know about dog/human relationships has come from the careful analysis of dog burials and human/dog interments. However, too often dog burials go unreported because they have not been recorded properly in the field. I am absolutely certain there are far more dog burials encountered than ever get mentioned in archaeological site reports.

I suspect there are two simple reasons for this failure to record dog burials adequately in the field. First, while archaeologists always get some training in the identification of human bone and are taught proper excavation procedures for human burial remains, they rarely if ever receive instruction in recognizing deliberately interred dogs. It is hard to recognize a dog burial if you do not know what a dog bone looks like. Second, it is unlikely you would treat any dog burial you encountered as something special unless you understood a bit about the history of dogs.

You would have to understand that dog burials were significant before you would bother giving them extra time and attention in the field. As a result, many dog interments have gone unreported in field notes, or have been minimally described. I suspect many dogs found interred with human remains have been bagged as “fauna” along with other animals remains, the special relationship of the dog bones to the human burial lost forever.

Why archaeologists need to better appreciate dog burials

1) A unique spiritual relationship between dogs and humans has existed since the dog became a distinct species 12,000-14,000 years ago: dogs have a special cultural significance that other animals do not.

2) Dog burials are a manifestation of the dog/human relationship: we must have a more complete inventory of dog burials worldwide.

3) With some exceptions, dog burials and mixed human/dog burials can be expected in virtually any archaeological site 12,000-14,000 years old or less that has good bone preservation, regardless of locale.

An example

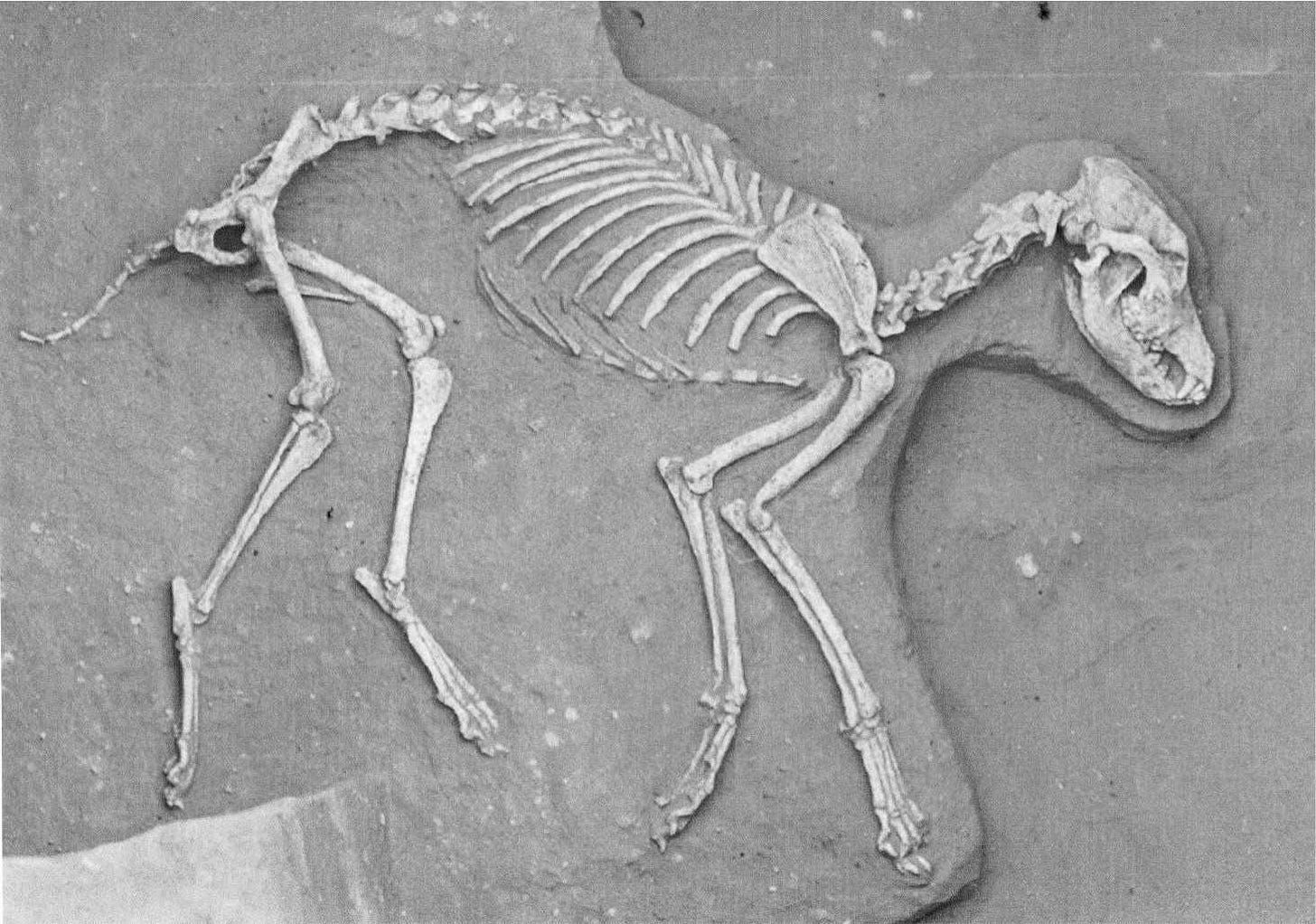

Subsequent analysis of the remains shown in the above burial image was undertaken by Dody Fugate of the Museum of New Mexico in 2004. This is her detailed description of the find:

The dog was found in an extramural pit next to a pit house. The dog was a taller dog than most found during this time. He was more gracile with a 'greyhound' face. He was between 7 and 10 years old and had been injured several times the last injury was probably what killed him. His teeth were in very good condition for a dog that old. He had not been skinned. I am wondering if these injuries could have been inflicted by someone or something other than his owners.

The dog had been buried very carefully and showed evidence of care and good food in his tooth condition but he had been bashed in the head at some time and had long ago healed broken ribs. He also showed arthritic damage to his toes resulting in his being very slow at the end. He was last injured by an attack to his hindquarters that broke several processes of his lumbar vertebrae and really messed up his rear ribs. Still, he lived long enough for his bones to have partially healed. Then he was carefully buried.

In summary, dogs were treated differently in ancient times: in life, they were often abused and left to fend for themselves. But at the same time, most ancient peoples seemed to believe that dogs possessed a powerful spirit that was released on their death. Archaeological remains of carefully buried dogs and dogs interred with people worldwide reflect this widespread belief, and provide a unique insight into the history of our long relationship with these animals.

The easiest thing you can do to support Biology Bites is to click the “♡ Like”. The more likes = the higher this post rises in the Substack feeds, which puts Biology Bites in front of more readers.

Dogs can tell us so much about the connections between people in the past. Not enough ancient DNA studies have been done. We know the large rocks of Stonehenge came from a number of places. I would like to know if the dog DNA fits the same patterns.