When Ancestors Withhold The Truth

Sometimes, the secrets our predecessors take to their graves can change everything

Diving into the details of your family history can be exciting and enlightening. However, there can also be disappointments and devastating surprises in store.

The worst, perhaps, are the hidden truths. When my sister took a deep-dive into our father’s family tree, she stumbled upon a secret that took our breath away.

It started innocently enough, with our famous 4th-great-grandfather.

William Crockford is considered the father of modern bookmaking. Born in 1776 to a London fish-monger, he made enough money gambling to bank-roll a unique gentleman’s club called Crockford’s in 1823.

William had noticed that the gambling establishments he frequented were too rough and low-class to attract men with real money. He came up with the radically innovative idea that if he gave the wealthy elites of Europe a place to gamble that was opulent and grandiose enough for them to feel really at home, with the best wine and food available—and made it by membership-only, to make it even more exclusive—he could fleece them blind.

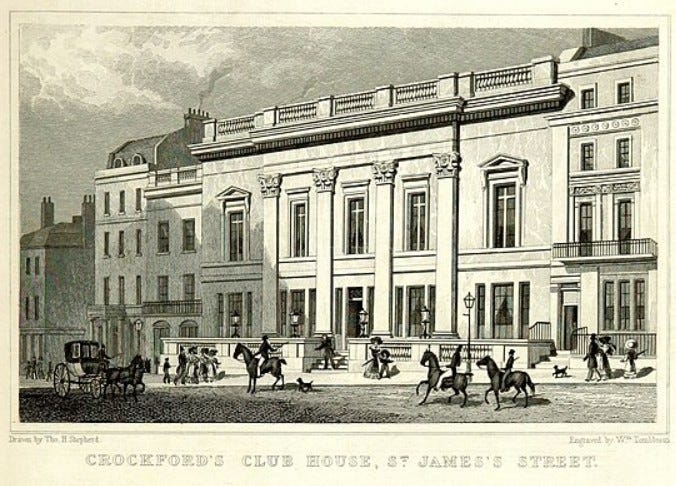

He situated his gambling club on St. James Street in central London, a few convenient blocks up the road from St. James Palace, which was still in rather regular use by the royal family.

In short order, all of the wealthiest men of British and European society belonged to Crockford’s club, including the Duke of Wellington, Benjamin Disraeli, and a plethora of Lords and Barons. Many of the most active gamblers were young and bored, as well as rich. The club was a huge success and turned lower class Crockford into a millionaire. He essentially bought himself into the British aristocracy in a way no one had ever done before, which did not please the upper class very much—in part, because his success brought some of those families close to bankruptcy.1

Crockford purchased a home in the exclusive complex at Carlton House Terrace opposite St. James Park in London, which I found out recently was just next door to the 4th-great grandfather of my friend and biology colleague, Lord Matt Ridley. Crockford’s were in #11, Ridley’s ancestor’s in #10. Their children may even have played together (if it was allowed—so, probably not).

Crockford also bought a farm in Newmarket, where he raised race horses.

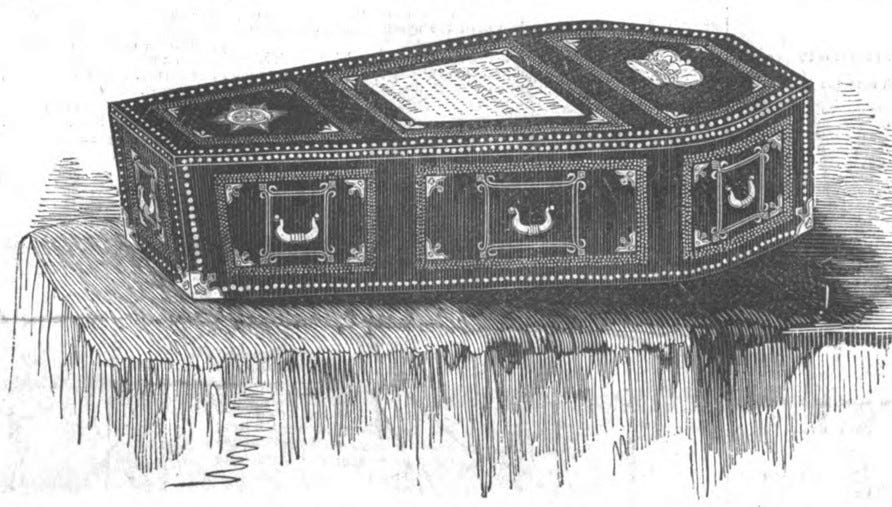

William Crockford sired 14 children from two wives, of which Felix (the youngest) was the line leading to me. William died in 1844 but before his death purchased a family vault in the catacombs beneath the recently-opened Kensal Green Cemetery. He commissioned for himself (or left instructions for his wife to do so), a velvet-covered coffin similar in style to the one used to bury the Duke of Sussex, who died the previous year, and the Duke of Wellington’s, who died eight years later.

I visited the crypt in 2014—170 years after his death—on my way back from Russia with my many-times removed cousin John, who now holds the deed. William Crockford had been one of the first to purchase an underground vault in the new cemetery back in the mid-1800s and I expect his chosen position at the end of an aisle, adjacent to one of the open-air light shafts, would have been premium-priced (see the photo I took below).

Spooky doesn’t even come close to describing the catacombs—I didn’t even know such places still existed. Obviously not designed for living visitors, we picked our way through the passages following the glow of a single flashlight held by the caretaker. With the camera I had, even with a flash it was too dark to take pictures anywhere else except at Crockford’s vault at the end. Talk about the light at the end of a tunnel…

As for the Crockford family fortune, it was all rather down-hill from the millionaire state for the boys, although the girls faired a bit better. The older boys had been given a leg-up by their father on various business ventures before his death, but few of these seem to have panned out well enough to provide financial security. Frederick, the eldest, managed the club after his father retired in 1840, then established himself as a successful London wine merchant (for a time, at least).

On his death, William’s estate went to his wife, who seemingly helped the boys out a few times as well. But on her death, she passed what remained of Crockford’s gambling club wealth along to her daughters, the only ones who seemed to have had enough money-sense to keep their heads above water throughout their lifetimes.

As for Frederick, in 1854 he devised a business venture during the Crimean War to sell luxury goods to British officers. With the help of his youngest brother Felix, they filled a ship with beer, wine, liquor, and other desirable items, which they sold at an officer’s canteen near Sebastopol (Balaklava Harbour) as the war raged on around them, as described by Charles Dickens for the Daily News in 1855:

The first ship-full of goods sold well but the Crockford boys had the misfortune of bad timing: they could not offload their second shipment (apparently purchased with borrowed money) before a peace treaty was brokered. Frederick was forced to declare bankruptcy and escaped debtors prison with only, quite literally, the shirt on his back.

Penniless but perhaps again bankrolled by one of the sisters, Frederick headed to Canada and bought a farm near Orillia, Ontario. [Why Orillia? We’ll never know.] He found himself a wife and fathered a gaggle of children.

For Felix, our direct ancestor, the story gets murky as the paper trail thins: as best can be determined (through the brilliant ancestry detective work done by my sister), Felix fathered a son by a woman he met during the Crimean adventure (who we affectionately call “Maria from Crimea”). For reasons that remain undocumented, he ended up with custody of the child, who was called Anthony.

With no real marketable skills, Felix’s only income was a small stipend from his oldest sister Fanny. As this seemed to be barely enough to keep him alive without working, he no doubt struggled with the added burden of keeping a child.

When young Anthony was about 10 years old, Felix took the boy on a boat across the Atlantic to see his brother Frederick—and left sometime later, without the child. Anthony appears to have stayed on at the farm in Orillia until he was about 14 and then ran away. He found a woman, changed his name to Thomas (perhaps to avoid some debt or other illegality?), and fathered three boys, the oldest of whom (also named Frederick) was my grandfather.

Felix Crockford died virtually penniless in 1896 at the age of 70 and is ironically buried in the local cemetery of the small south-west town in England where my cousin John now lives. We think older sister Franny must have paid for his plot and marker, which had disappeared by the time John found the gravesite. John paid the considerable cost of replacing the marker in 2014 and you can see below how the bright white cross stands out amongst its 19th century neighbours at the back of the cemetery.

The three boys fathered by Anthony/Thomas (son of Felix), remained in Ontario and eventually settled in Toronto. There, my grandfather Frederick Crockford married my grandmother, a Latvian immigrant, and they had two sons.

You must be asking by now: What’s the secret and why did it matter?

There were two related secrets, both the kind of lies-by-omission that pepper many family histories because the truth is too painful to bear. But ultimately, it was one really big one.

The reality was, Frederick Crockford was not the biological father of either of the two sons born to his wife in Toronto. Not only did my father and his brother have different fathers, we don’t know for sure who either of them were.

The key piece of evidence: WWI-era miliary medical records that indicate my grandfather had undescended testicles. This meant, without treatment, he was incapable of fathering children (because the inside-body temperature is too high for sperm to survive—that’s why testicles are external in mammals).

This startling evidence was supported by an Ancestry DNA test my sister took which revealed no relationship to one of the children of my father’s brother (which should have shown a first cousin relationship) but instead gave strong links to an entire extended family of unknown ‘others’—for both of them. Neither of the two cousins showed any relationship to Crockfords descended from William the gambling club owner.

To be fair, there were always suspicions that something odd had gone on, simply because my father was so different physically from his brother - and his parents. A rape, perhaps, or even an affair early in the marriage that resulted in my father’s birth? But no one suspected both boys were illegitimate.

So many questions…

Did my grandfather know he could never have children? Did the army doctors tell him what his condition meant? It seems improbable that even if the doctors hadn’t enlightened him on the implications of his missing ornaments, his fellow soldiers wouldn’t have filled him in, whether sympathetically or not. Rather a hard detail to hide under the shared living conditions of war, I imagine. Really, he must have known.

But did he tell his wife-to-be before they married or wait until later?

My sister, the sleuth, discovered my grandparents had been married for 10 years before my father was born, which strongly suggests my grandfather knew but didn’t tell his wife until suffering almost a decade’s worth of childlessness became more than she could bear.

Perhaps he never told her at all but rather, she finally figured it out. The fact that her husband had missing equipment must have been obvious but if she’d never been with another man, would she even have known that wasn’t normal? Or, that it mattered to successful reproduction? Perhaps she simply learned—from a book, a doctor, or a more enlightened female friend—that a man without testicles couldn’t father a child.

Regardless, after nine years of marriage without getting pregnant, she appears to have taken matters into her own hands.

However, the logistics—in the 1920s—of her managing to get pregnant not just once, but twice, would have been daunting, which suggests a high degree of motivation. It meant she either had to have sex with two men who were not her husband or find a way to artificially inseminate herself with sperm from two other men—knowing that her husband would immediately understand that any pregnancy indicated she had done one or the other.

It’s possible, I suppose, that she didn’t do this deliberately. Perhaps she thought she was the one with faulty reproductive equipment, became unhappy in her marriage and had an affair that left her pregnant by surprise—and then did the same thing again four years later, with another man, who also got her pregnant.

Regardless, having two different fathers certainly explained why my father and his brother were so off-the-charts dissimilar in physical features. Uncle Dave (the younger of the two), a Viking-like blonde with piercing blue eyes who stood over 6 feet tall; my father (the first-born), small and Gypsy-like (5’ 7” or so): dark haired, brown-eyed, and swarthy complexioned. Both of my grandparents were blonde and blue-eyed.

My grandmother’s subterfuge also explained so much of what we knew about the family’s dysfunctional dynamic.

My grandfather was viciously abusive to both boys, which to me is strong evidence he knew the children were not his own and didn’t take kindly to my grandmother’s decision. Even if no one else knew that he wasn’t their father, he did. And even if he’d initially agreed to the plan—it seems more likely she was furious he’d withheld that information and simply told him she would find a father somewhere else—it was obvious he very quickly came to resent the existence of the children.

The family lore was that his nastiness came from having been abandoned (along with his siblings) by his mother when he was 10 years old—that he’d grown up in one of the hell-holes that orphanages were at the turn of the 20th century and that this had damaged him psychologically. In reality, his two brothers spent a few years in an orphanage but he did not.

He did come home from the war with what they called “shell-shock” (now PTSD) and other mental health issues, but it appears in relation to these children, he had what he considered to be a legitimate grievance.

My father told my step-brother (who’s 10 years older than me), that the abuse at home was so bad he essentially went to school at age 5 and never went home until he absolutely had to. His mother could not—or would not—protect him from his father’s beatings. Initially, he simply arrived at school as early in the morning as he dared and stayed afterwards as late as possible.

However, his father had also refused to pay for the meager supplies required to attend school (a pencil and a notebook), which was a big problem. Someone must have told my father that the Catholic church paid their choirboys, which turned out to be his ticket out of the family madness.

My father sang in the Toronto Christ Church Cathedral choir from his first year of elementary school until he graduated from high school. The choir not only supplied the extra money he needed to survive his school years, but practices and performances gave him a place to go evenings and weekends, which minimized his exposure to his father’s wrath. He might even have paid his father some of his wages to placate him and perhaps even covered the cost of his younger brother’s supplies when it came time for him to start school.

I suspect my grandfather had also become abusive with my grandmother, who then came to resent the children she appeared to have gone to such lengths to bring into the world. All we know is that at some point she also became abusive to the boys.

Although joining the choir saved my father, it left his younger brother even more exposed to the violence. Dave was four younger and never figured out how to keep himself safe. Perhaps he too could have joined the choir but refused. All we really know is that Dave endured the abuse as long as he could, dropped out of school and left home early—and eventually became a vicious wife-beater himself.

My father managed to break the cycle of abuse by figuring out, at a very young age, how to protect himself. Later, he was able to pluck his brother’s wife and children out of the abject poverty and abuse, but it was too late to save his brother.

My grandmother’s secret would not have been discovered if not for the sleuthing of my sister, which she might have been less likely to have undertaken without the enticement of our famous gambling club forefather. My grandmother knew who the fathers of her two children were but kept it to herself, even on her deathbed (both she and my grandfather lived into their 90s). We know the children were indeed hers—and not adopted—because the DNA evidence traces back to her Latvian and Russian ancestors.

Hidden illegitimate pregnancies are, of course, nothing new in many (if not most) families. Accidents happened, as did affairs and even rape. But this took the phenomenon to a whole new level.

Unfortunately, it left my sister and I severed from the family history we grew up knowing, made worse because it’s the family line whose name we carry—and a famous name, at that.

Sadly, English cousin John—who I took such pleasure in coming to know over my extended visit in 2014 and again when he visited Canada in 2016—is actually not a blood relation at all, despite the name we share. We stay in touch as affectionate cousins, as if we’d never learned that fact. However, deep-down, we know the family ties are broken.

I’ve had to accept that I’ll not be buried in the Kensal Green vault alongside William Crockford—as John had once graciously offered—which is a rather big disappointment for me. It had seemed a fitting way to close the family circle by bringing a long-lost Crockford back to London after all these years. But neither John nor I are willing to pretend ignorance of the fact that we do not actually share a Crockford ancestor: you can’t unlearn the truth.2

Yet, if I’m not really a Crockford, who am I? Who was my father’s father?

My sister found a potential biological grandfather via the DNA testing which ties us to American relations of the Pennebaker family, a few of whom had moved to Ontario in the early 1900s. One male relative worked as a pharmacist in the same Toronto neighbourhood where my grandparents lived in the 1920s. Beyond that, we are ignorant of who my grandmother consorted with 100 years ago.

That said, 100 years have passed and it’s time to give breath to the truth. I do miss being able to claim William Crockford as a 4th-great-grandfather, because I felt a strong affinity with him as an outside-the-box thinker. However, I fall back on the knowledge—untainted by my grandmother’s indiscretion—that my father had an innovative mindset all his own, which didn’t end with singing his way out of an abusive relationship.

I am his daughter, and for me, that’s enough.

Would I have rather not known? I’m not really sure. Blood relationships matter (because, of course, genetics) but family is also shared history. My grandfather’s medical condition and my grandmother’s subterfuge only truncated the genetics. My grandfather was a legitimate Crockford, gave my father his name, and raised him—albeit badly—as part of the Crockford family.

I think perhaps that should count for something.

The easiest thing you can do to support Biology Bites is to click the “♡ Like”. The more likes = the higher this post rises in the Substack feeds, which puts Biology Bites in front of more readers.

Dash, M. (2012). “Crockford’s Club: How a fishmonger built a gambling hall and bankrupted the British aristocracy: A working-class Londoner operated the most exclusive gambling club the world has ever seen.” Smithsonian Magazine, November 29. http://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/crockfords-club-how-a-fishmonger-built-a-gambling-hall-and-bankrupted-the-british-aristocracy-148268691/

There’s plenty of spots left in cemetery plots owned by my mother’s side of the family, so it’s not that I’ll have no final resting place for my ashes, if anyone even bothers to do something with them. I’d have only gone the casket burial route for a spot in the Crockford family vault because I think it was what my father would have wanted for himself, if he’d been given the chance.

Dr. Crockford ==> Magnificent story -- and even true. My wife and I are avid genealogists and have done work for FamilySearch photographing 200 year-old registers of births and marriages in the Caribbean.

One of my claims to fame is my great-uncle Bruno, who was a "human-cannonball" in a circus.

Susan. I think you have outdone Agatha Christie.