Why I changed my opinion about a 33,000 year old possible early dog

Available facts changed and it was clear my initial assessment was premature, so I corrected the record.

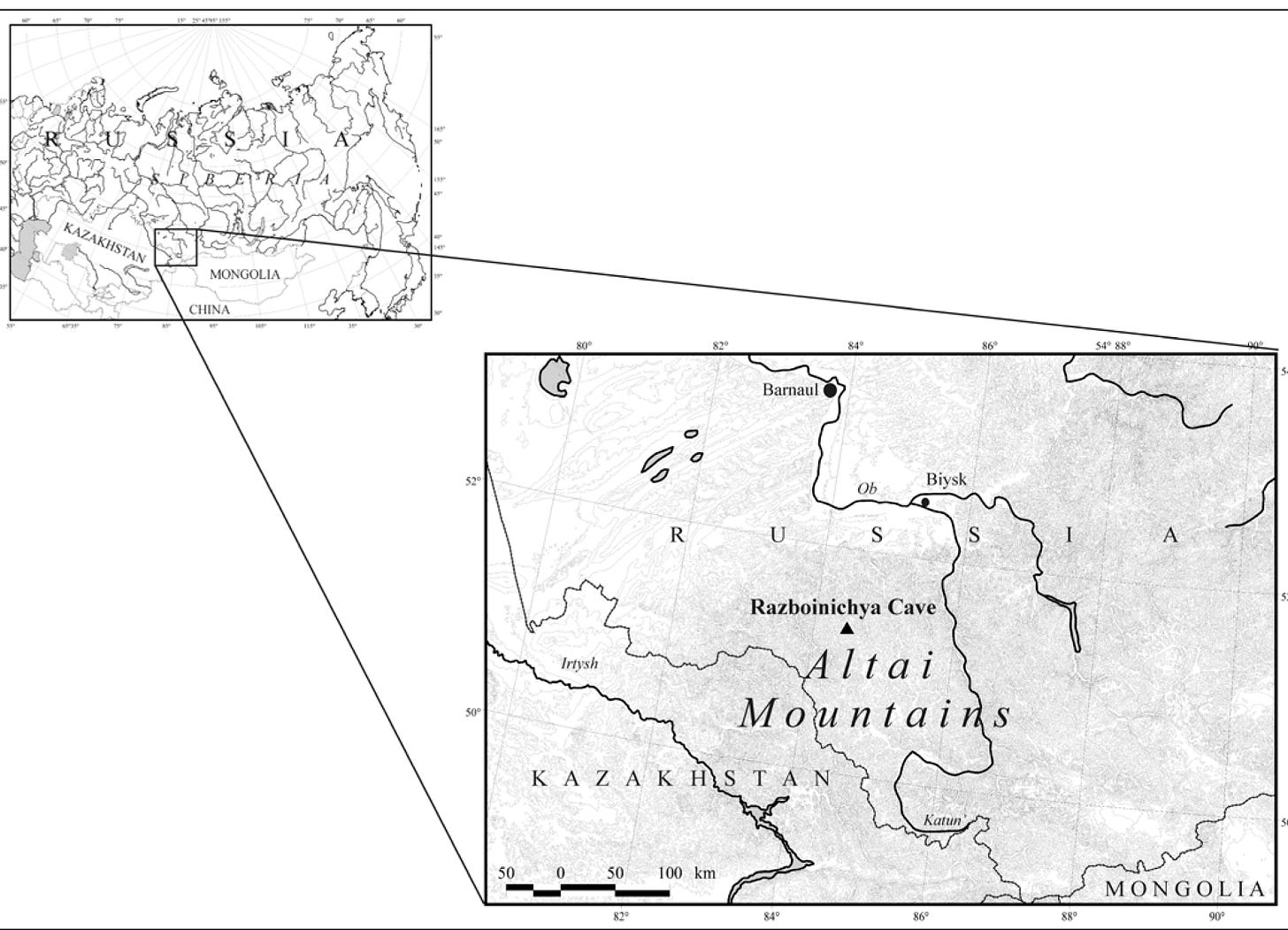

Back in 2009, I was contacted by a colleague in Siberia about a dog skull he thought might be the oldest known domestic dog specimen. I agreed it looked enough smaller than a wolf to be promising but thought it might be an early version of a domestic dog that didn’t leave any ancestors.

However, before we were able to get our analysis published, a specimen of similar age and type was reported from Belgium and claimed without reservation to be an early dog. Our paper was eventually published in July 2011, with archaeologist Nikolai Ovodov – who had originally found the specimen – as lead author.1

In contrast to the Belgium group, however, we included in our paper all the measurements we’d taken from the Siberian specimen and referred to our specimen as a possible “incipient dog.”

Our press release read, in part:

A 33,000-year-old dog skull unearthed in a Siberian mountain cave presents some of the oldest known evidence of dog domestication and, together with an equally ancient find in a cave in Belgium, indicates that modern dogs may be descended from multiple ancestors.

It is now possible to suggest that the process of dog domestication began several times in different parts of Eurasia in the Upper Paleolithic but failed to persist. Both the Goyet and Razboinichya individuals appear to represent such incipient dogs. Recovery of new specimens may change this story, Crockford says, but that’s part of what makes archaeology so interesting.

The paper got an extraordinary amount of media attention, and most of the interviews fell to me: CBC, NPR (“Science Friday”), BBC, Macleans Magazine (Canada), National Geographic, National Post (Canada), among many others worldwide.

However, another paper published by the Belgium authors just six months later made us realize that critical measurement data of several ancient canid specimens, which had not been included in their 2009 paper, had led us to a questionable conclusion about these Upper Palaeolithic canids.2

I knew we had to correct the record.

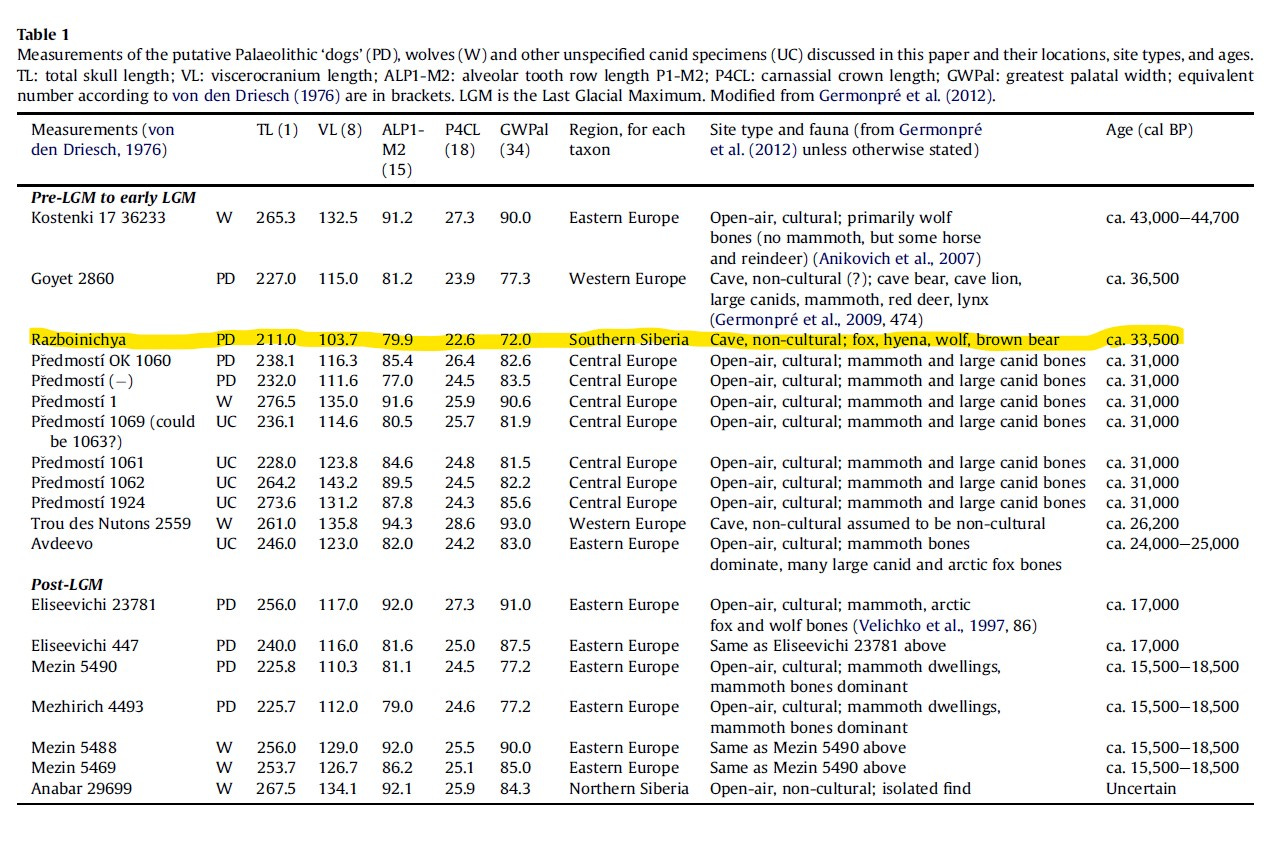

It was clear that the data (copied below, in a table from our 2012 critique, our Siberian specimen highlighted) did not support a finding that these pre-Ice Age specimens were examples of even incipient dogs – even though the Belgian authors, led by palaeontologist/archaeozoologist Mietje Germonpré, insisted they were fully domestic dogs.

Co-author Slava Kuzmin and I prepared a “comment” to the journal in response. We knew our resounding criticism of these colleagues might be resisted but were astonished to discover the journal editor had sent our critique out to eight anonymous reviewers! I’d never heard of a paper assigned eight reviewers.

However, in retrospect, I think the editor made the right call. It meant that a diversity of concerns about our assessment were addressed before publication, which made it a fair and persuasive evaluation.3

After the critique was published, I received emails from several colleagues commending us on the paper, as well as saying, “thanks for doing this, so I didn’t have to!”

We concluded, in part:

We need more specimens from Palaeolithic sites with numerous wolf bones described in full – not just the complete skulls or the dog-like ones, but mandibles and post-cranial elements of all adult individuals…Until then, we contend that the evidence to date is rather compelling that the ‘Palaeolithic dogs’ described by Germonpré et al. (2009, 2012) and the ‘putative incipient dog’ described by Ovodov et al. (2011) may simply be rather ‘short-faced’ wolf individuals that lived within a population of typical wolves that interacted in various ways with human hunters.

While the dog-like morphology of some Late Pleistocene wolves may have arisen due to persistent interactions with people over varying lengths of time, it is misleading to call this relationship ‘domestication.’

Juliet Clutton-Brock, who for decades had been the world’s foremost domestication expert as well as a former curator at the Museum of Natural History London – and whom I consulted with before writing our critique – said the following to me via email in early 2012 (just three years before she died):

I have also come round to the view that what we are seeing with the so-called Upper Pleistocene “dogs” are wolves that have a morphological adaptation in the skull and teeth to scavenging rather than hunting and feeding upon carcasses of megafauna [large animals].4

That said, this issue remains a contentious one, especially for Germonpré and her co-authors, who continue to insist that fully domestic dogs arose before the last Ice Age (aka the Last Glacial Maximum, LGM, about 20,000 years ago) and colleagues other than myself continue to challenge this assertion.5

In retrospect, I believe Dr. Kuzmin and I should have also published a stand-alone version of our paper elsewhere – in other words, one that was not a “comment” published in the same journal – because I’m sure it would have had a broader impact. At the time, none of our more experienced colleagues suggested this step and it’s only now that I see this was a missed opportunity.

However, the results of a study using computer power to compare the sizes and shapes of a huge sample of ancient wolf and dog skulls – which I had a small hand in producing – should be published soon. It provides additional support for my 2012 assessment that those pre-LGM canids were wolves, not dogs (incipient or otherwise).

I’ll keep you posted.

Ovodov, N.D., Crockford, S.J., Kuzmin, Y.V. et al. (2011). A 33,000 Year Old Incipient Dog from the Altai Mountains of Siberia: Evidence of the Earliest Domestication Disrupted by the Last Glacial Maximum. 2011. PLoS ONE, 6 (7): e22821 https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0022821 [open access]

Germonpré, M., Sablin, M.V., Stevens, R.E., et al. (2009). Fossil dogs and wolves from Palaeolithic sites in Belgium, the Ukraine and Russia: osteometry, ancient DNA and stable isotopes. Journal of Archaeological Science, 36 (2), 473-490. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jas.2008.09.033

Germonpré, M., Láznicková-Galetová, M., and Sablin, M.V. (2012). Palaeolithic dog skulls at the Gravettian Predmostí site, the Czech Republic. Journal of Archaeological Science, 39 (1), 184-202. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jas.2011.09.022

Crockford, S.J. and Kuzmin, Y.V. (2012). Comments on Germonpré et al., Journal of Archaeological Science 36, 2009 “Fossil dogs and wolves from Palaeolithic sites in Belgium, the Ukraine and Russia: osteometry, ancient DNA and stable isotopes”, and Germonpré, Lázkičková-Galetová, and Sablin, Journal of Archaeological Science 39, 2012 “Palaeolithic dog skulls at the Gravettian Předmostí site, the Czech Republic” Journal of Archaeological Science, 39 (8), 2797-2801. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jas.2012.04.033 [contact me for a copy]

See for example: Leonard, J.A., Vilà, C., Fox-Dobbs, K., et al. (2007). Megafaunal extinctions and the disappearance of a specialized wolf ecomorph. Current Biology, 17 (11), 1146-1150. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2007.05.072 [open access]

Germonpré, M., Van den Broeck, M., Sablin, M. V., Láznicková-Galetová, M. et al. (2021). Mothering the orphaned pup: The beginning of a domestication process in the Upper Palaeolithic. Human Ecology, 49, 677-689. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10745-021-00234-z [open access]

Galeta, P., Láznicková-Galetová, M., and Sablin, M.V., and Germonpré, M. (2021). Morphological evidence for early dog domestication in the European Pleistocene: New evidence from a randomization approach to group differences. The Anatomical Record, 304(1), 42–62. https://doi.org/10.1002/ar.24500 [open access]

Janssens, L. A. A., Boudadi-Maligne, M., Lawler, D. F., et al. (2021). Morphology-based diagnostics of “protodogs.” A commentary to Galeta et al., 2021, Anatomical Record, 304, 42–62, doi: 10.1002/ar.24500. The Anatomical Record, 304 (12), 2673–2684. https://doi.org/10.1002/ar.24624 [open access]

See also: Bergström, A., Stanton, D.W.G., Taron, U.H., et al. (2022). Grey wolf genomic history reveals a dual ancestry of dogs. Nature, 607, 313–320. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-022-04824-9 [open access]