Oprah and Me: Ozempic vs. Diet and Exercise

Are drugs the solution to intractable obesity or do we keep fighting our fat demons?

Oprah and I share a birthday and a fight with fat

Oprah Winfrey and I don’t have much in common regarding financial success, political views, or general ideology. But we were born on the same day in 1954—and share a lifelong fight with fat.

Today, we both turn 71.

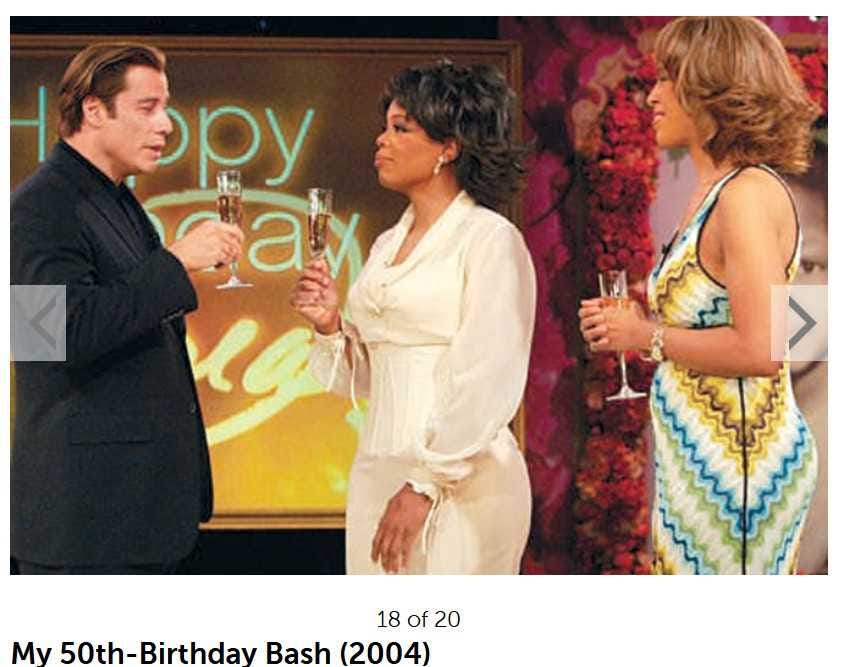

On our 50th birthday in 2004, I sat alone and mildly obese on my couch drinking a glass of inexpensive wine watching a slim Oprah celebrate the occasion on a TV special surrounded by Hollywood stars and champagne, as the photo above shows. Five years later, our physical fortunes had reversed: I was a fit and muscular size 10 (and quite happy with that result) and she was chunky yet again.

Oprah is a billionaire with limitless resources which she has used over the years to help get her weight under control using every diet imaginable. All her Weight Watchers marketing notwithstanding, Oprah has long been able to afford her own private gym and personal trainer to help with motivation, has had the means to hire a private chef to prepare all her meals and buy all the high-priced organic foods she might desire—even the money to pay for top-of-the-line therapists to help her deal with the root causes of her overeating. She also has her Christian faith to call upon.

However, even with all that at her disposal, she’s had less success over the years with maintaining a normal weight for any length of time than I’ve had, which isn’t saying much. Recently, facing the added challenge of being over 65 and obese yet again, in 2021 she resorted to taking a new class of drugs called GLP-1 receptor agonists (such as Ozempic and Wegovy) to help beat the fat.

Oprah hasn’t said which drug she’s taking, which is probably just as well. But combined with diet and exercise, her weight is back down again, while mine is not.

And at what we might as well call a late celebration of our 70th birthdays early last year, she hosted a TV special on the role this medication has played in her weight-loss journey, called Shame, Blame and the Weight Loss Revolution.

However, despite my frustrations over my life-long battle, this is a fad I can’t get behind.

I’m not even close to being a billionaire and couldn’t afford that medical option – reportedly costing around US$1000 a month – even if I thought it was advisable (which I don’t).

It has to do with being honest about what this fight entails and why it happens. I know how to eat without gaining weight, it’s just that sometimes, I fall off the wagon into a pit of despair filled with chocolate chip cookies. It’s not that the weight magically starts piling back on without me realizing why it happens.

But still, the issue is this: for decades, Oprah and I have been going back and forth—sometimes slim, sometimes overweight, and sometimes mildly obese. Over and over again, never managing a permanent change. The details of her story are here.

Interestingly, Oprah and I started from very different places. She wasn’t a fat child and was never really significantly fat: she simply obsessed about not being model-thin. A March 2024 essay relayed this story:

"I still have the check I wrote to my first diet doctor—Baltimore, 1977," Oprah Winfrey wrote in a 2002 essay for O magazine. "I was 23 years old, 148 pounds, a size 8, and I thought I was fat. The doctor put me on a 1,200-calorie regimen, and in less than two weeks I had lost ten pounds (there's nothing like the first time...). Two months later, I'd regained 12. Thus began the cycle of discontent, the struggle with my body. With myself."

I’d have been ecstatic to be a size 8!

When I was 16 years old, I weighed about 195lbs. I got up to around 210lbs when I left home at 20, but by the time I was 23 in 1977, I was happy to have gotten down to about 175lbs (a size 14). I was able to keep it there for at least the next five years, even after my first pregnancy.

Oprah has admitted she hit her all-time highest weight of 237lbs in 1992 (at age 38), while my highest was 230lbs in 2019 (at age 65). For about one third of my adult life, I’ve been well below that maximum, at or below 175.

I had some huge emotional issues growing up due to my younger sister’s congenital heart condition and was overweight from the time I was about 7 or 8 years old. To make a long story short (and without meaning to whine), our family dynamics changed dramatically in 1955 because my mother had to focus on keeping my critically ill baby sister alive when I was only 18 months old.

Virtually abandoned by my mother much of the time, I was almost totally dependent on my father and older brother, when they were around to provide it, for care and affection. After my dad died suddenly when I was 13, my mother moved my sisters and I across the country to Vancouver. My older sister soon left home, leaving me alone with my younger sister and mother—neither of whom had ever been an ally.

During my final two years of high school, we ended up on welfare when my mother gave up trying to find work. She became a slovenly alcoholic and my sister did nothing but watch TV and wait to die, since the doctors had told her she shouldn’t expect to live past 17. Trapped in a situation I could neither change or escape, I was frustrated and depressed as well as fat.

However, the Alaskan malamute my father had bought me when I was 11 kept me from flipping over the edge into morbid obesity because it kept me walking long distances every day. The walking was as good for my mental health as it was for keeping my weight under some kind of control.

For this reason, I later bought myself malamutes—another five different dogs over the years—until my kids left home when I was 50. After that, I learned to go for a walk or a run by myself and for myself, which I consider a huge life-style accomplishment.

I’ve managed my many weight losses by calling on a strong work ethic. I never tried extreme diets. I had no psychological help, diet advisor, or fitness trainer: I did my own soul-searching (including talk therapy with friends), devised my own diets, and learned not just how to exercise but how to motivate myself to exercise—except last year, when my daughter and I successfully motivated each other as we worked towards dropping a few dozen pounds each before her wedding.

I kept myself from morbid obesity by always fighting back from the brink, time and again—something my 450lb uncle (my mother’s brother) was sadly never able to do.

The best I’ve managed is about five years of normal or near-normal weight, which I’ve achieved three times: once in the late 1970s, again in the late 1980s-early 1990s and from 2007 to 2012 or so. The slimmest I’ve been was the last time, when I got down to a perfect size 10 which I maintained for two full years. I inched up to a size 12 about 2009 but I was able to keep it there over the next three years or so, despite a painful injury.

Then I totally fell off the wagon when a romantic relationship went sour and gained another 40-50lbs in a few months. It happens so fast!

I figure I’ve lost and regained more than 500lbs during my lifetime (in small and large bursts). Despite that, I’ve always been healthy. I’ve never had high blood pressure, even at my highest weight or during my two pregnancies. I don’t have diabetes or even pre-diabetes. My pre-surgery medical work-up six years ago ahead of my hip-replacement didn’t reveal any cardiac issues either.

The problem is that when I get depressed—and lose hope as well as my sense of self-worth—there’s an anxiety that takes over that blocks out rational thought about food. I consider that anxiety to be a mental health issue, not a character flaw.

I’ll tell you a story that helped me understand why this keeps happening. In the middle of an ugly divorce in the late 1970s that involved a restraining order, my spouse called me at work and said if I didn’t come home, he would shoot our two dogs. I fell apart. A colleague heard me sobbing hysterically in the office next to hers, unable to think what I should do.

She gave me a few Valium (diazepam) tablets she had with her, telling me to take only one quarter at a time as they were very strong. The panic that was causing my hysterical crying lifted within minutes and I realized what I needed to do was call my lawyer. Over the next few days, I could feel the panic rising again as the Valium wore off and subside as it kicked in. However, by the time I ran out of pills, the situation had been resolved and the angst had subsided, so I didn’t need them anymore.1

However, a couple of months later, something set me off again and I could feel the anxiety rising. Without Valium to turn to, I ate a bag of cookies instead. I was utterly astounded to find it had exactly the same effect: cookies quelled the panic.

I realized then that my entire life, I’d been self-medicating my anxiety with food. Something about my brain chemistry meant that a shit-load of fat and sugar had the same effect as Valium, which we know is massively addictive. I suspect it works that way for a lot of folks who battle obesity.

Perhaps I should have sought out my own source of Valium but I never did. At any rate, I didn’t turn to habit-forming drugs then and now, there’s a different option that’s not technically addictive but might as well be, because you have to keep on taking it to keep the weight off.

Ozempic and Thyroid Hormone

This new medical solution to obesity has become a fad that the rich and famous like Oprah are embracing with gusto. Drugs like Ozempic co-opt a class of drugs developed in 2017 to treat type 2 diabetes, called Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1RAs). In biochemical terms, agonists crank up production.

GLP-1 and GIP are hormones released by special endocrine cells in the gut during a meal. They are partially responsible for prompting the release of insulin from the pancreas and influence the brain (especially the hypothalamus) to send a “stop eating” signal. These hormones bind to specific receptors, which together are required to prompt the release of insulin and trigger the brain responses.

The receptors are found throughout the body, including the pancreas (where insulin is produced), kidneys, stomach, brain (including the hypothalamus), and portions of the thyroid gland not involved in hormone synthesis.

Receptor agonists like Ozempic cause more of these receptors to be released than would normally be the case, resulting in a greater activation of the complex gut-brain signalling. This markedly slows digestion.2

In other words, your stomach is almost always full, so you can eat a lot less without feeling that you’re being starved (even though you actually are).

GLP-1 receptor agonists include formulas that can be taken twice a day (like the drug exenatide, marketed as Byetta) and which activate the GLP-1 receptor for only a few hours, while long-acting preparations activate the receptor continuously (generically called semaglutude, marketed as Ozempic, Wegovy, and Rybelsus; the liraglutide, marketed as Victoza and Saxenda, and the dulaglutide, marketed as Trulicity).

Dual-action medications are available that activate the GLP-1 receptor and a similar one (gastric inhibitory polypeptide, or GIP), which includes the drug tirzepatide (marketed as Mounjaro).

However, these drugs come with side effects, the most common of which are vomiting, diarrhea, constipation, and excess gas—which are said to often subside after a few weeks of use. Less common downsides are inflammation of the pancreas (pancreatitis), heartburn, vision changes (diabetic retinopathy), bowel obstruction, gallstone attacks and bile duct blockage, fainting, fever, anaphylaxis, seizures, and bloody urine, among others.

There seems to also be an increased risk of thyroid cancer and, over the long-term, potential loss of skeletal and heart muscle.3

A big red flag for me is that the Mayo Clinic website indicates these drugs should not be taken by those with a history of depression or women who are pregnant (or plan to become pregnant).

The warning about depression comes partly because the slowing of digestion may impact the absorption of any antidepressants being taken but also for the direct impact of these drugs on the brain, via its known effects on the hypothalamus. One very recent, real-world study (October 2024) found a marked increase in risk of depression, anxiety, and suicidal behaviours in people taking GLP-1 drugs (including a 195% increase risk of major depression and a 108% increased risk for anxiety), which was worse for those taking high-dose formulations like Wegovy.4

These GLP-1 drugs also appear to affect thyroid function. A literature review by Capuccio and colleagues in 2024 reported that some studies found a decline in thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) with GLP-1 RAs. [Recall from my previous essay that TSH levels are how doctors traditionally measure thyroid function: high TSH indicates low thyroid function (hypothyroidism), while low TSH indicates a revved up metabolism (hyperthyroidism).]

Researchers note that the weight loss itself might be causing the TSH decline via some unknown mechanism, the fact that they don’t really understand how these drugs impact thyroid function is another issue of concern.5

It seems to me that there’s a reasonably good chance that these popular GLP-1 drugs, especially taken long term, could alter thyroid function or mask important clinical signs of thyroid disfunction.

The fact that these drugs should not be taken while pregnant is something no woman of child-bearing age should ignore, but even if you’re not, a drug that’s not good for a developing foetus is probably not good for anyone.

Most critically, perhaps, is that if drugs like Ozempic are incompatible with depression, it should put them out of reach as a weight-loss option for many obese and overweight people, for whom depression or anxiety are the underlying reason for being fat in the first place.

Battling the Obesity Demons

I’m not convinced by the argument that obesity is a disease, or that there’s an “obesity gene.” If there’s anything that comes close to being an actual disease involved here, it’s likely to be depression or other mental health issues, like anxiety.

And rather than an obesity gene, it’s far more likely that some kind of complex hormonal interaction comes into play. Something like stress triggering a drop in thyroid hormone, which triggers anxiety and a reduced availability of T3 to the brain but which excess feeding resolves by stimulating the release of anxiety-calming serotonin.6

I suspect a very large number of obese people (whether they yo-yo diet or not) are dealing with some traumatic incident in their past – even many traumas – and use vast quantities of food as the easiest means to relieve their anxiety. Watch a few episodes of the reality TV show, “My 600lb Life,” and you’ll notice the pattern.

Not all children will respond to a trauma by over-eating, of course. But is that because only some individuals are uniquely vulnerable to using food as a drug or because not all traumatized kids discover that eating a bag of cookies or a huge portion of macaroni and cheese alleviates their angst? That’s the million-dollar question.

Not all children will have had the option of discovering the drug-like quality of binge eating, especially if access to food was restricted in their home, or if tight budgets meant there was simply not enough food around to make over-eating possible.

I was simply overweight (not obese) in the early 1960s and routinely dropped 10lbs or so during the summer when I could run around and swim every day. However, I clearly had learned to binge eat to relieve my anxiety, which makes me wonder if, when I was still a toddler, my father or older brother (not knowing any better) had given me a handful of cookies to make me stop crying because my mother was busy with the sick baby.

I didn’t really enter obesity territory until I was in high school: not only did my stress levels increase, but I had babysitting money I could use to feed my addiction.

For most people, the cost of food eaten at home and their access to restaurant food has changed markedly since the 1960s. Relative to today, food consumed a higher proportion of families’ budgets than it does today: the cost of food dropped from 14% of household budgets in 1960 to 5.6% in 2013, for food prepared at home.

However, people are now eating unhealthy options outside the home (especially fast food) much more often than they did in the 1960s, even though the cost of doing so has risen enormously. In other words, we are relatively wealthier than we were then and much of that increased wealth is being spent on food.

Greater access to less-healthy food options means that those inclined to binge-eat to treat their mental health issues are finding it easier to do so. As a consequence, many more people have fallen off the edge into morbid obesity, from which it’s almost impossible to escape.

Some people have indeed let their weight get out of control because they haven’t paid enough attention to what they were eating and failed to exercise. These people often become self-righteous after they’ve reversed their bad habits. They and others without a weight problem glibly call all fat people lazy and insist if they can maintain a normal weight, anyone can.

However, these people were never using food as a drug to self-medicate anxiety. They simply can’t understand the mental health issues involved because they never developed a truly addictive relationship with food.

My personal experience has convinced me that high-fat and high-sugar foods cause obesity not because they are inherently “toxic” (as some people are insisting) but because they can be biologically addictive: they act on the brain like a drug to relieve anxiety, and in that respect are no different than medications like Valium.

The only effective way to treat the addiction is to deal with what’s causing the depression and anxiety. This is a lot harder than it sounds and I’d bet money that even professional therapy seldom yields a permanent fix.

For most people, it works until you hit a stress you can’t deal with and fall off the wagon. If you can’t get a handle on the backsliding within a few days, it rapidly spirals out of control. As you eat more and exercise less, the pounds pile on with demoralizing speed, which makes you even more depressed.

This hamster wheel ride can go on for years before you manage to get it stopped.

That’s why I suspect the Ozempic solution is not a reasonable, long-term alternative for people who’ve had a life-long battle with fat: if you’re already conditioned to ignoring your body’s “I’m full” signal, taking Ozempic to amplify this signal is not going to work, especially if it also increases your depression or anxiety.

In other words, declaring that these drugs are a miracle cure for obesity, even for some people, is premature. Not withstanding the disturbing side effects, there simply hasn’t been enough time to judge their long-term safety and efficacy. Surely we’ve learned enough from Covid-19 vaccines to be very sceptical of new drugs with overly-optimistic claims?

Given her quick acceptance of these drugs, I would have guessed that Oprah also embraced the mRNA vaccine in 2021. A quick Google search confirms she did and also encouraged others to do the same despite the obvious red flags, which to me is the mark of a fad-follower, not a critical thinker.

My most successful weight-loss and weight-maintenance strategy was something I learned from my daughter in late 2006: the trick is to never let yourself get hungry by eating six or seven small, high-protein meals a day totally about 1400 calories. If you think about it, this effectively does what Ozempic-type drugs accomplish by stimulating the release of “stop-eating” hormones.

Partnered with an hour of aerobic exercise (walking or running) in the morning plus 45 minutes of weight training or more walking in the evening—almost 2 hours of daily exercise in total—this approach had me dropping dress sizes at a dramatic rate without feeling deprived.

I ached almost all the time from the workouts but I wasn’t obsessively thinking about food I shouldn’t have. I was fit and emotionally healthy enough to keep things in check even when I broke my arm in 2009. It worked for me like a charm for years.

Until it didn’t.

That said, on this, my 71st birthday, I seem to be on track to get my weight back under control despite the limitations of old age. Problems with feet and joints mean I can no longer exercise as intensely as I used to, which means the weight loss is bound to be slower. But that’s OK. I can also accept that I’ll likely never be a size 10 again.

I’ll be happy just to get out of the plus-size category, and that’s certainly do-able.

Oprah can have her slimmed-down, 71-year-old, drug-induced body: time will tell if she retains it much longer than she ever did before the drugs. I’m not shaming or blaming her for turning to drugs: I’m just not convinced that three years (2021-2024) is long enough to be declaring this approach a resounding success.

I intend to keep plodding away, working to keep my demons at bay through rational thought, regular exercise, and intellectually satisfying projects because I know from experience that these strategies are effective.

My struggle with my food addiction is part of who I am but only a small part. It never stopped me from being a good mother or building a successful career. I can’t help but feel that continuing to work at this relationship with food will give me a gratification that taking a drug like Ozempic can never provide.

My follow-up essay on this topic will focus on the recent dramatic rise obesity that coincidentally mirrors a similar increase in anxiety and depression, especially in children.

Do you believe in coincidence?

I know many readers can’t afford to pay the monthly subscription fee for every Substack account they enjoy. But since it’s my birthday, maybe some of you free subscribers would like to make a small, one-time donation? I would very much appreciate the support.

The easiest thing you can do to support Biology Bites is to click the “♡ Like”. The more likes = the higher this post rises in the Substack feeds, which puts Biology Bites in front of more readers.

Calcaterra, N.E. and Barrow, J.C. (2014). Classics in chemical neuroscience: Diazepam (Valium). ACS Chemical Neuroscience, 5(4), 253–260. Open access https://doi.org/10.1021/cn5000056

Capuccio, S., Scilletta, S., La Rocca, F., et al. (2024). Implications of GLP-1 receptor agonist on thyroid function: A literature review of its effects on thyroid volume, risk of cancer, functionality and TSH levels. Biomolecules, 14(6), 687. Open access https://doi.org/10.3390/biom14060687

Martens, M.D., Abuetabh, Y., Schmidt, M.A., et al. (2024). Semaglutide reduces cardiomyocyte size and cardiac mass in lean and obese mice. JACC: Basic to Translational Science 9(12), 1429-1431. Open access https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacbts.2024.07.006

Wilding, J.P.H., Batterham, R.L., Calanna, S., et al. (2021). Impact of semaglutide on body composition in adults with overweight or obesity: Exploratory analysis of the STEP 1 study. Journal of the Endocrine Society, 5(Supplement 1), A16-A17, https://doi.org/10.1210/jendso/bvab048.030

Kornelius, E., Huang, JY., Lo, SC., et al. (2024). The risk of depression, anxiety, and suicidal behavior in patients with obesity on glucagon like peptide-1 receptor agonist therapy. Scientific Reports 14, 24433. Open access https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-75965-2

Capuccio et al. (2024), above.

Kirkegaard, C. and Faber, J. (1998). The role of thyroid hormones in depression. European Journal of Endocrinology, 138(1), 1-9. https://doi.org/10.1530/eje.0.1380001

What a journey. My heart goes out to you. Have you come across the fructose survival hypothesis, from Johnson and colleagues out of colorado? They've published 5 or 6 papers in the last couple of years, one of which aims to unify the theories of obesity. It's an interesting perspective - also considers certain mental health problems and their correlates with non-communicable disease.

I wrote about it in children here, but one thing that I'd love to see explored further is the threshold effects and the temporal component: https://open.substack.com/pub/guenbradbury/p/the-biggest-return-on-investment?utm_source=share&utm_medium=android&r=4bpym1

This all sounds right based on my experience. Another way to reduce stress is to donate to a worthy cause, which instantly makes you feel better.